Culture Anthology Presents

On the power of culture and the internet

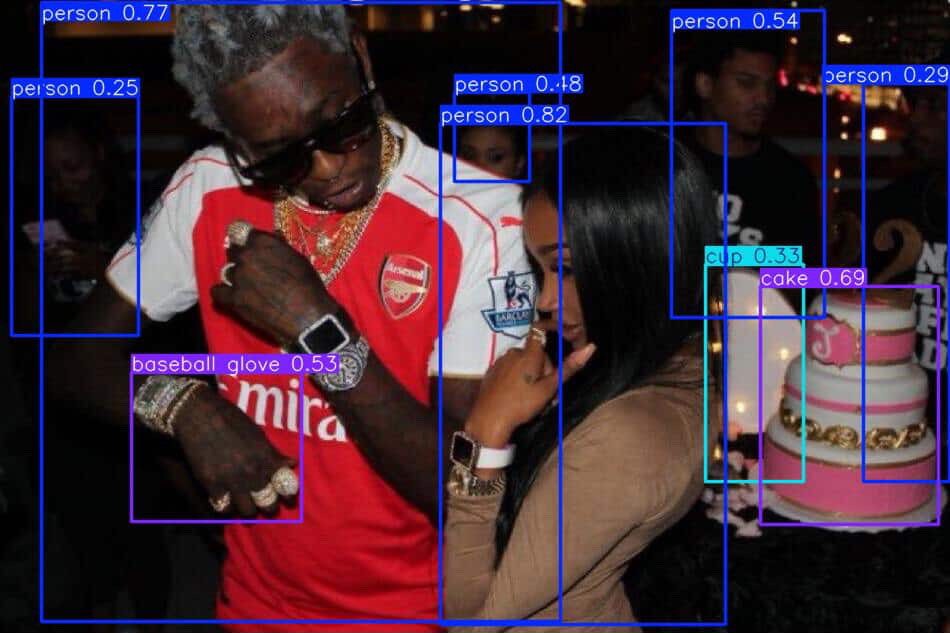

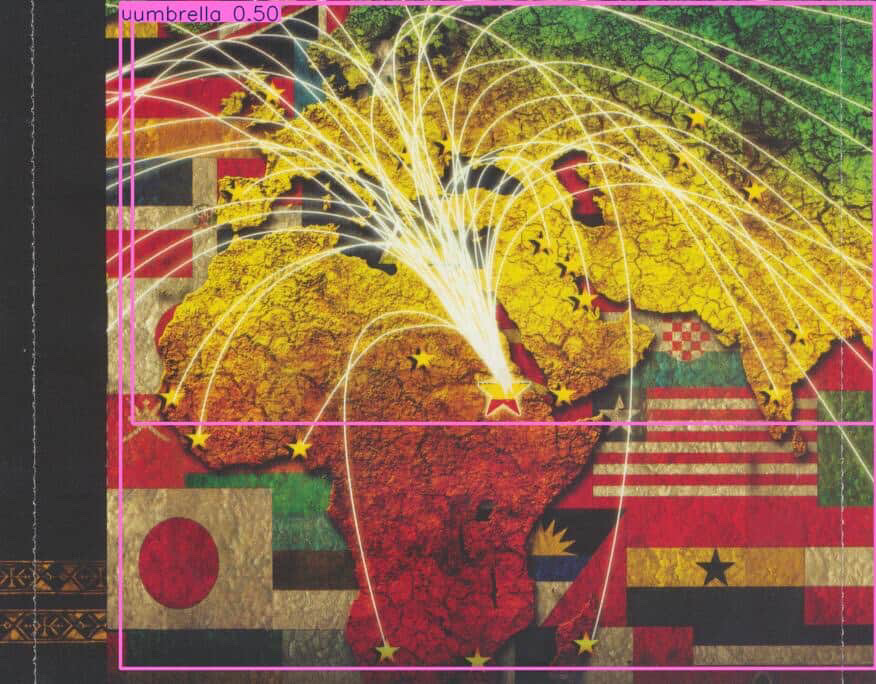

Picture two digital voyagers piecing together a living archive—an interactive map of Black culture that beats with memory, rhythm, and diaspora. This is Lingo of the Black Atlantic, the creation of Chigo Ibekwe (Chi) and Isaac Dakin. It’s less a project than a soundscape—woven from images, codes, and cultural poetics.

What started as an online bond has grown into an immersive portal: a space where visuals collide and reassemble, sparking dialogues that stretch from Lagos to Harlem, the Caribbean to London. Each click becomes a verse, each image an echo, building a digital Black Atlantic that refuses to stay still—fluid, boundary-breaking, and unapologetically alive.

Culture Anthology is stepping into that space with you. Meet the duo who are reshaping what it means to archive, remix, and inhabit culture in the digital age. This isn’t just documentation—it’s transformation

Q1: For those who may not know you yet, could you introduce yourself? Tell us about your background, your creative practice, and what drives the kind of work you do.

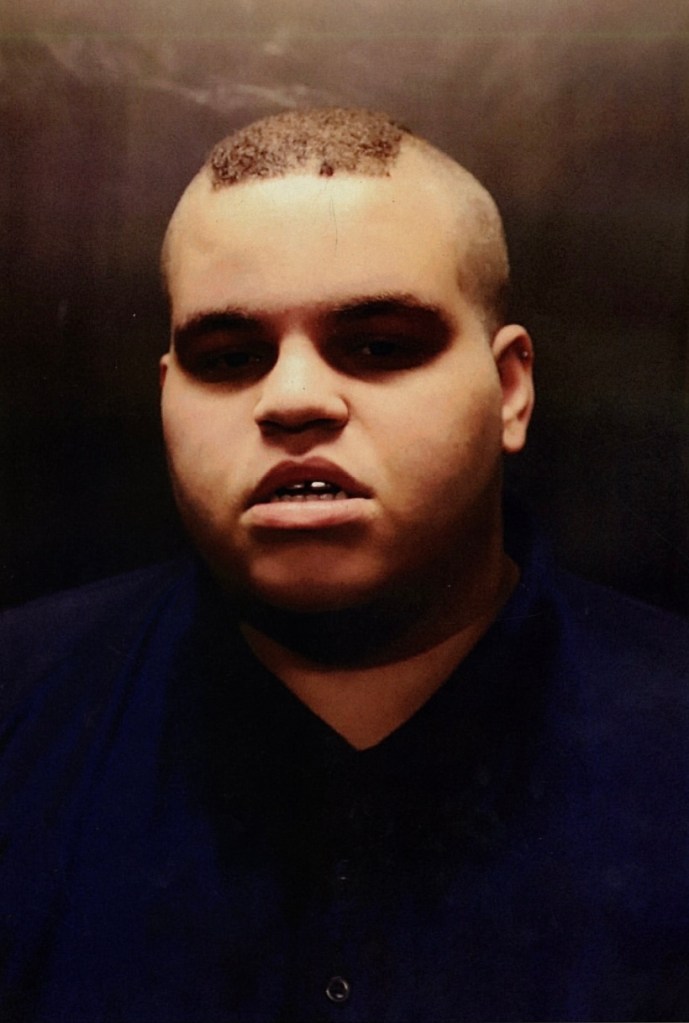

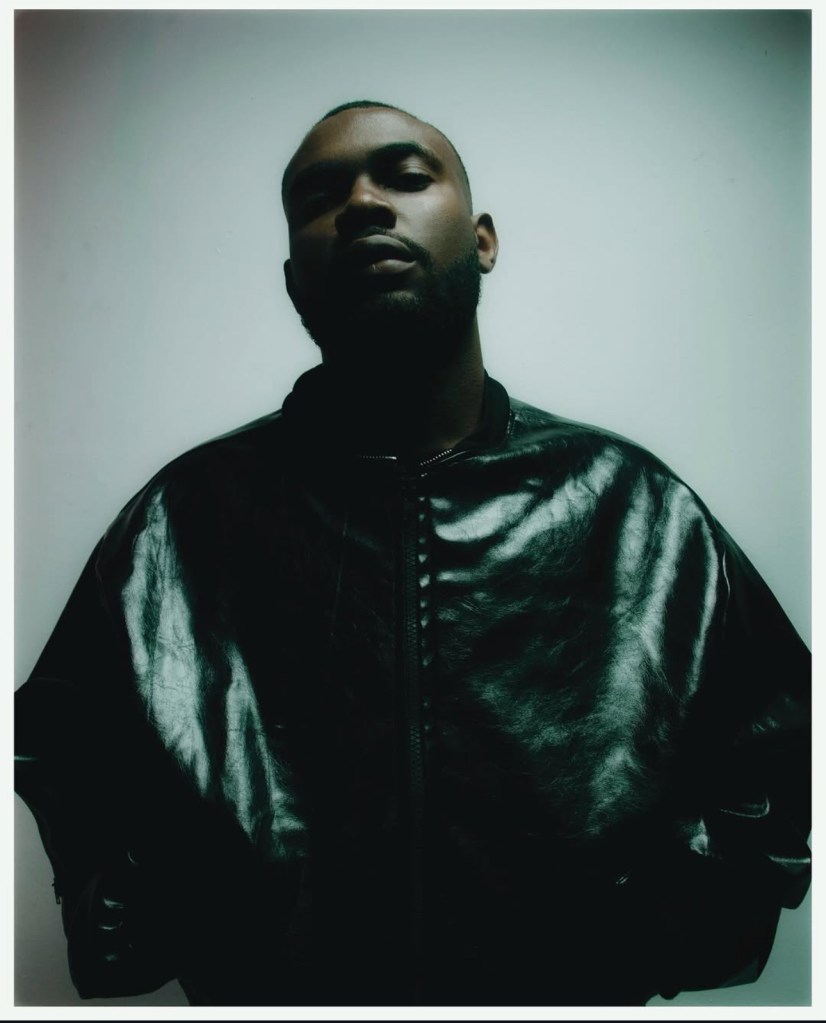

ISAAC:My name is Isaac. I grew up across the UK, Australia, and Germany, so I’ve had quite a global upbringing. I’m currently studying Fashion Communication at Central Saint Martins. A lot of my work is influenced by academic and theory-based perspectives, rather than purely focusing on aesthetics—though aesthetics also play their own role in a different way

CHI: My name is Chi. I grew up in Lagos, where I’ve lived my whole life. I studied English and Literature, and like Isaac, I’m drawn to bringing an academic lens into my work—but in a way that feels accessible to a wider audience. I’m also very interested in challenging and breaking away from the Western gaze.

Q2: Can you share how Lingo of the Black Atlantic came to life? What inspired it, and what is the core aim or purpose behind this work?

ISAAC: I think what’s important to establish is that what we’re doing, and what we want to keep doing, is very much linguistic in nature. It’s a language—mainly visual, with some written elements—but primarily a visual language. What sparked the project for us was the excitement of seeing if the fluency we share in our conversations could exist on a wider scale. Even though we approach things through very different lenses, we still find common ground, shaped by a shared drive for something bigger. So the project became this open-ended research process, producing different outcomes and directions. It blurs the lines between our personal work, our collaborative work, and even things that fall into the project unexpectedly. At its core, it’s really about creating a broader umbrella to see who else can connect with this language and spark dialogue around what we’re trying to express

CHI: For me, it’s tied to the fact that I live in Lagos, Nigeria—a former British colony. Going back to what I said about breaking the Western gaze, I feel like once ‘African art’ became global, there was this unnecessary pressure for African artists to constantly explain or emphasize their ‘Africanness.’ Personally, I grew up online, on the internet, so when I see works that lean heavily into referencing ancestors or nature, I often can’t relate. That expectation creates a kind of stigma or limitation. What I’m really interested in is breaking that mold—showing that culture is fluid. My experiences of being raised in a former colony, with full access to the internet, all merge together and shape the way I see and create

Q3: Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic talks about culture as something fluid, constantly moving across borders. How do each of you understand your own cultural background in relation to that idea?

ISAAC: For me, that realization came a few years ago when I started university. I remember having conversations with my friends about how the internet has broken down the idea of authenticity, and how authenticity as a way of assigning value has become outdated. You can be a kid in a village anywhere in the world in 2025 and tap into punk—you don’t need to have lived in London in the late ’70s, worn Vivienne Westwood, or gone to punk concerts to embody it. People often talk about this as the ‘death of subculture’ because of TikTok and micro-trends, but in reality, these platforms just make it easier for people to access and express what resonates with them, without boundaries.

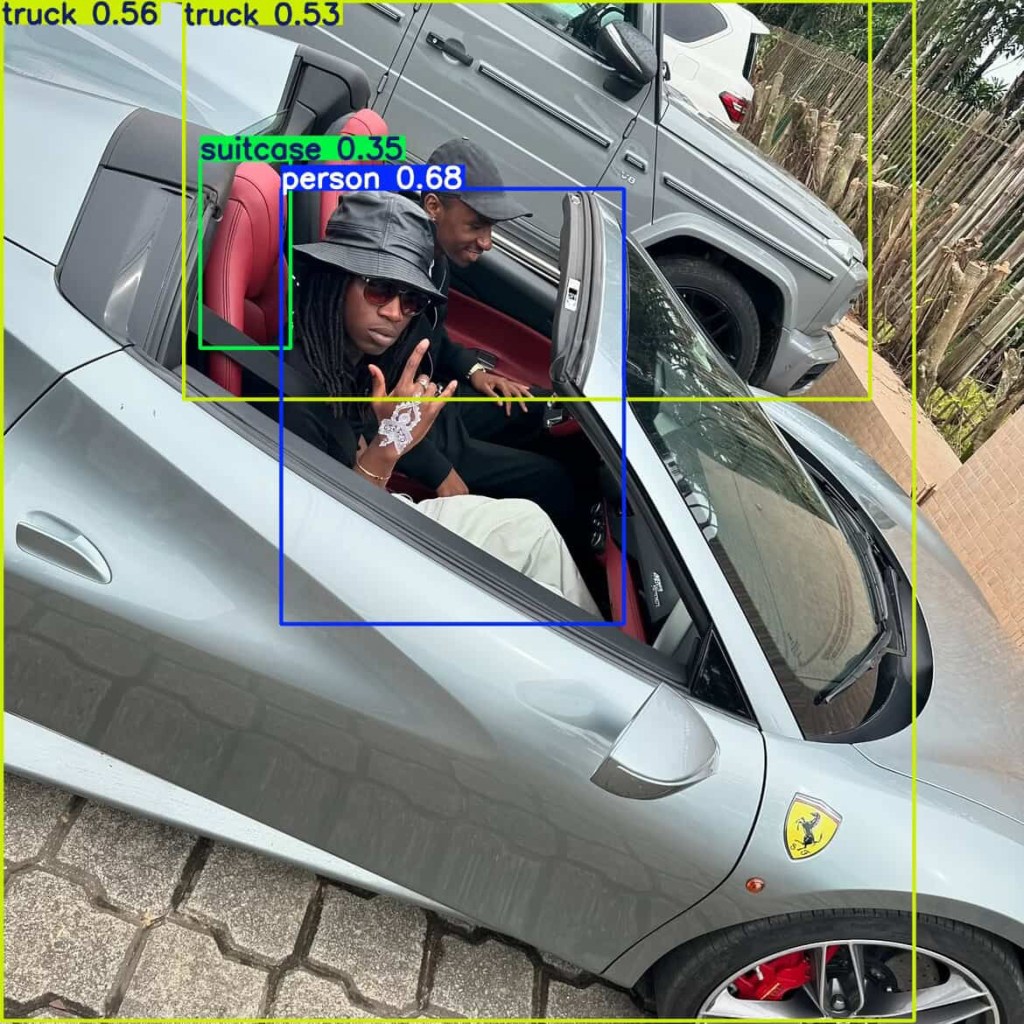

That shift really highlighted cultural fluidity for me. Before reflecting on it, I struggled to tell the stories I wanted to tell, because I felt limited—as if I could only create from what was personally close to me. But over time, I learned to take more ownership and freedom, exploring ideas I felt were relevant even if others couldn’t immediately see their relevance. For example, when I went to Nigeria in 2024 and took photos on an old iPhone 5, it was about capturing something that spoke to me in that moment, beyond the usual expectations of what stories I ‘should’ tell

CHI: The idea of statehood itself was something imposed—defined by colonizers—and it’s still something people are grappling with today. That realization really struck me. It made me think about how fragile and constructed these boundaries are, and how much of our sense of identity has been shaped by systems that weren’t created for us in the first place. For me, that pushed the idea of cultural fluidity to another level. It became less about simply blending influences and more about questioning the frameworks that claim to fix culture in place. If the nation-state itself is a colonial invention, then culture, by nature, resists being boxed in. That’s why I feel driven to explore cultural fluidity in its most radical sense—seeing it not just as movement between styles or references, but as a deeper challenge to the structures that try to define who we are and how we belong

Q4:The word “lingo” itself is about slang, codes, and shared language. How do you see Black culture online today creating its own “lingo” that connects people across continents?

ISAAC: I’ll let Chi speak on this more since it’s really his territory, but for me, something that’s always stood out is the way these linguistic overlaps reveal themselves online. For instance, I’ll be scrolling through Twitter and see what looks like a regular Black Twitter post—written in Black American English—and then I’ll open the replies and suddenly, they’re all in Pidgin. It’s this moment of realization, like, oh—this is actually a Nigerian sphere, even though it’s seamlessly sitting on my feed. Or sometimes it’ll be a thread about a Black English footballer, and again, the replies are in Pidgin. Those moments really highlight the way these digital spaces collapse borders and carry multiple Black linguistic worlds at once. But I’ll let Chi expand on that, because it’s very much his bag

CHI:For me, it’s also a very intuitive thing. Sometimes I’ll be researching a topic, or even just thinking out loud about it, and then suddenly it shows up on my feed. And when I go through the posts, I’ll see French voices, German voices, Nigerian voices—each speaking in their own terms, their own language. But somehow, it all still makes sense to me, and it all connects. That’s what fascinates me: how different cultures and linguistic spheres cross paths in these digital spaces, even when they don’t technically belong to the same sphere. It shows how fluid the cultural conversation really is, how these worlds overlap without needing to be neatly aligned

Q5: Black culture has many centers—African, Caribbean, Black American, Afro-European—and sometimes they clash as much as they connect. How did you negotiate those differences when building Lingo?

ISAAC: We definitely made a conscious choice to strike a balance, even if it wasn’t something we explicitly discussed at length. I do remember thinking that, at the end of the day, we’re both invested in politics and aware of the global dynamics at play. The United States, for instance, still exerts a kind of hegemony over the world, and by extension, over the internet—it’s where it was invented, and much of its infrastructure and culture still originates there. Because of that, a lot of the imagery, memes, and viral content that circulates online tends to be Black American voices—they’re the ones amplified the most. That naturally became a path we followed. But that doesn’t mean we wanted the project to be exclusively American. It was more about recognizing that reality, while consciously seeking to include and reflect broader perspectives

CHI: I think, in a way, the internet has a strong American imprint, and a lot of the Black cultural content that circulates there comes from that context. But what’s interesting is that not all the images we include are explicitly tied to Blackness. Some of them might seem unrelated at first, yet they still contribute to a dialogue. For me, it’s not about creating a clash or forcing a connection—it’s about letting these images coexist and resonate in ways that spark thought and conversation.

Q6: In your view, how does the history of the transatlantic — migration, slavery, movement — continue to shape the ways we speak, dress, and express ourselves today?

ISAAC: Something that’s always resonated with me—first subconsciously, and later reinforced by things I’ve read—is the idea that music was the one thing people brought with them on slave ships. For me, music becomes a fundamental way we connect; it underpins everything. That’s why it’s always been central to our project. Whether it’s using an original rap track for a website launch video or sharing clips of rappers, music is our lens, our framework—it answers so much of what we’re exploring.

I’m also fascinated by how Pidgins and Creoles have historically functioned. They’re forms of language that emerged under specific circumstances, and I think about the ways I can repurpose words, ideas, or structures from them—sometimes playfully, sometimes provocatively—in my work with images and video. It’s about exploring how language, music, and culture intersect, and how those intersections can shape the work we create today

CHI: Yeah, like Isaac said, music just transcends. Before we even dive into it, I’d say it’s a form of resistance. A perfect example is Baby Keem—he uses auto-tune in a way that feels like a completely new language he’s inventing. To me, that’s what makes music so powerful—it’s often the answer, the medium through which ideas, identity, and resistance can be expressed.

Q7: As an artist and cultural worker, what has this project taught you personally about your own relationship to language, heritage, and Black culture?

ISAAC: I think one thing I’ve learned—and what’s made collaboration so rewarding—is that working closely with someone else has allowed me to care less about constraints and take risks I wouldn’t take on my own. Collaboration creates that freedom, and I guess taking risks is really the only way to make meaningful work

CHI: Collaboration has been central to this whole project, and it’s something I’ve started to bring into my own work. I think it reflects the nature of creativity in the 21st century—how ideas are shared, remixed, and expanded through collective effort. This project really pushed me to embrace that approach. I also have this obsession with unpacking and understanding what Black people and the diaspora have contributed culturally, and working on this has brought me closer to understanding that

Q8: What do you see as the main aim of this project? What kind of impact or conversation did you hope to start by documenting the “lingo” of the Black Atlantic?

ISAAC: Personally, I don’t approach it with a fixed aim. For me, it’s more about exploration. Ultimately, you share your work to see who it resonates with—that’s really all you can hope to achieve, and all you can strive for.

CHI: Personality-wise, I’m just following what’s happening and observing. I’m not approaching it with a specific goal for the project—it’s also a way for me to understand myself.

Q9: How important has the community been in this work? Are there particular collaborations, voices, or cultural exchanges that were central to shaping the project?

ISAAC: Community is incredibly important to us. A lot of the project has been just the two of us, but we’ve also brought others into the process—friends contributing text, Dope on sound, Pax for a quick verse in the video. What we really wanted was to collaborate with people who are pushing the same ideas we are, whether they realize it or not. Someone like Pax, for example, is exploring Nigeria and Switzerland through an Afro-European lens, which aligns perfectly with what we’re trying to do. And of course, Dope has been a close friend for a long time, and his work intuitively understands the power of imagery and sound. For us, it’s crucial that collaborators not only grasp the importance of diaspora and cultural perspective but also resonate with how we use imagery and sound to communicate it

CHI:Isaac said it all—community is absolutely central to the project. It provides a space for people to share perspectives on different cultural experiences while staying open to new ideas and interpretations

Q10: What’s next? Do you see Lingo of the Black Atlantic as an ongoing conversation, or is it a chapter that opens onto new projects you’re dreaming of?

ISAAC and CHI : We’re working on a book that mirrors the way we see the website. The website is interactive and dynamic, and that interaction will feed directly into the print version. Early on, we debated whether print was aspirational or if we were undervaluing the digital experience, but we realized that going digital first and then translating it to print makes the most sense. Of course, it’s not the ultimate or final Black Atlantic project, but it’s a way to transition without giving away all of our sources.

A lot of what we do is experimental and spontaneous. For instance, on our Instagram, we might post something that started as a design experiment for the book, like a poster with a logo over someone’s head. Sometimes someone will suggest, ‘let’s just post it,’ and we tweak it slightly and share it. Growing up on the internet, we understand that you have to put in to get out—you share, you experiment, you take risks. You never know what’s going to resonate with people, and that freedom to be spontaneous is a big part of how we work

ISAAC AND CHI’S SHOUTOUTS:

Shoutout to Lamzy—he’s like our secret third horseman, even though we haven’t officially revealed that yet. But he’s definitely a part of it.

Chi, thank you for sharing your vision and your voice with us today. Lingo of the Black Atlantic reminds us that culture is always in motion — shaped by history, rooted in memory, but constantly reinvented by us. For those listening, you can follow Chi’s work on Instagram @markingsofahomee, and explore the project online at blackatlantic.net.

This was In the Cut, presented by Culture Anthology.

see you next week, guys!

Perrine

© 2025 Culture-Anthology

Leave a comment